China’s Deepening Property Downturn Signals Prolonged Recovery Ahead

China’s Deepening Property Downturn Signals Prolonged Recovery Ahead

By

David Goldfarb

Last updated:

October 10, 2025

First Published:

November 30, 2025

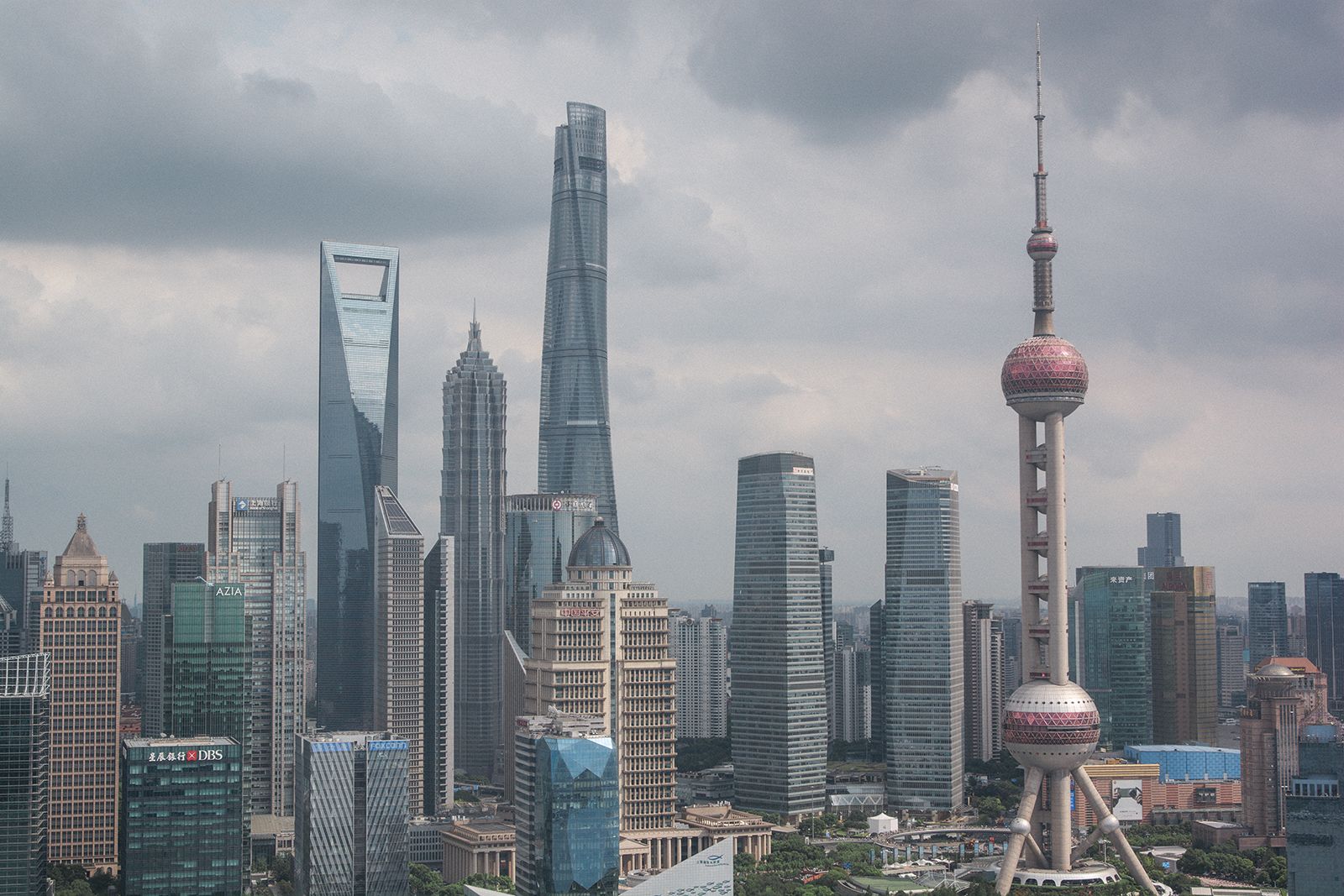

Photo: CNN

China’s real estate sector, once a cornerstone of its economic expansion, is now facing a deeper slump than anticipated. According to S&P Global Ratings, new home sales in 2025 are projected to fall by 8% year-on-year, reaching between 8.8 trillion yuan and 9 trillion yuan (approximately $1.23 trillion to $1.26 trillion). This marks a significant downward revision from the 3% decline S&P had predicted in May, extending the housing market’s contraction into a fifth consecutive year.

The property sector’s persistent weakness underscores the scale of challenges confronting Beijing as it struggles to restore confidence among homebuyers and stabilize a market that once accounted for nearly 25% of China’s GDP.

Fragile Sentiment and Limited Policy Response

S&P’s analysts attribute the deteriorating outlook to fragile buyer sentiment and a slow pace of government intervention. “Homebuyers are still hesitant,” explained Edward Chan, Director of Corporate Ratings at S&P Global. “The government will need to continue supporting the sector and stimulate demand to rebuild confidence.”

Despite calls from Chinese leaders to “halt” the real estate decline, the policy response has been tepid. The five-year loan prime rate, a key mortgage benchmark, has only been reduced by 10 basis points so far in 2025 — a stark contrast to the 60-basis-point cut implemented in 2024. This signals that Beijing is taking a more conservative approach to monetary easing even as the sector remains under pressure.

In August, local governments in Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen announced partial rollbacks of property purchase restrictions, allowing families to buy additional homes. However, most of these incentives applied to outlying suburban districts, where demand remains weaker. Analysts say this targeted easing may not be sufficient to spark a broader recovery in housing demand.

A Market Shrinking to Half Its Size

The numbers illustrate the scale of the decline. China’s property sales have plunged from 18.2 trillion yuan in 2021 to an estimated 9 trillion yuan or less this year — effectively halving the market size in just four years.

S&P further projects another 6–7% decline in sales for 2026, with primary home prices expected to fall 1.5–2.5%. This persistent weakness highlights how far the sector has drifted from its once-booming phase, where surging urbanization and speculative buying drove decades of rapid growth.

As of August 2025, completed but unsold housing inventory had risen to 762 million square meters, up from 753 million just eight months earlier — evidence that supply continues to outpace genuine demand. “The government has assured people that unfinished apartments are being completed,” Chan said, “but the real issue now is that overall national demand is far weaker than expected.”

Construction Woes and Confidence Crisis

A central reason behind the prolonged downturn is the erosion of public trust in developers. For years, Chinese homebuyers routinely purchased properties before construction was completed. But as major developers like Evergrande and Country Garden encountered financial crises, projects were left unfinished, shattering confidence and triggering mass protests from affected homeowners.

In response, Beijing introduced a “whitelist” financing mechanism in 2024, directing funds to finish stalled projects. While this measure helped avoid a systemic collapse, it did little to spark new demand or address the fundamental oversupply issue.

At the same time, declining household income growth and high youth unemployment — which hit 17.5% in mid-2024 before official data was suspended — have further weighed on buyers’ willingness to take on long-term mortgage commitments.

The Government’s Balancing Act

Beijing finds itself walking a tightrope. On one hand, authorities want to prevent a housing crash that could trigger widespread financial instability; on the other, they are wary of reigniting a speculative bubble. The result has been piecemeal policy easing — just enough to stabilize developers, but not enough to fuel a meaningful recovery.

Premier Li Qiang acknowledged in August that the property downturn “remains unresolved” and emphasized the need for more targeted support. However, analysts caution that any large-scale bailout risks undermining Beijing’s efforts to shift economic growth away from property dependence toward manufacturing and high-tech innovation.

Still, there are minor signs of stabilization. According to S&P, sales among China’s top 100 developers edged up 0.4% year-on-year in September 2025 — the first positive reading in months. Yet, given the broader weakness, analysts believe this uptick represents temporary relief rather than a sustained rebound.

Looking Ahead: A Smaller but Stronger Sector?

S&P’s report concludes that the end result of this structural correction may be a smaller but healthier property market, as weaker developers exit and stronger firms consolidate their positions. The next phase of China’s property evolution will likely depend on whether policymakers can effectively balance stability with reform.

Economists expect that Beijing may cut policy rates further in early 2026 and expand funding to complete existing projects, but without a major revival in buyer sentiment, recovery could remain slow and uneven.

For now, China’s property market — once the engine of national prosperity — continues to drag on consumer spending, local government revenues, and investor confidence. Unless substantial measures are taken to reignite demand, the slump could extend well beyond 2026, shaping a new normal for one of the world’s largest real estate markets.

Popular articles

Subscribe to unlock premium content

London’s Gourmet Playgrounds

From Bean to Buzz in Thailand

The Secret Life of Pop-Up Luxury Restaurants in Paris

London’s Gourmet Playgrounds

From Bean to Buzz in Thailand

London’s Gourmet Playgrounds